Casey Flaherty of Baker McKenzie explores the ideas and thoughts behind incremental improvements and how they hold weight. Depending on the situation at hand, there may not always be one clear answer.

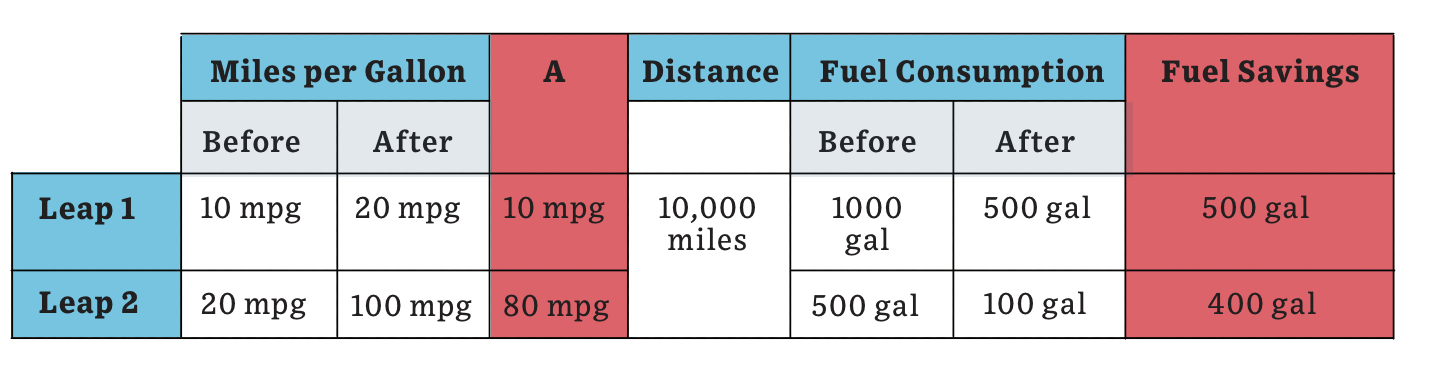

At the recent, excellent Law 2030, Vijay Govindarajan observed, “There is only so much Six Sigma you can do.” Despite my affinities, I concur. Low baselines can have an outsized impact on the efficacy of interventions— but then baselines stop being low. Consider buying a car with an eye towards better gas mileage. Which technological leap saves more gas? Improving a car’s miles per gallon (i) from 10 mpg to 20 mpg or (ii) from 20 mpg to 100 mpg? Put another way, from the perspective of gallons saved, what is the ‘bigger improvement’ (i) +10 mpg/2x or (ii) +80 mpg/5x? Since I’m asking the question, you already surmised the answer is counter intuitive:

One simple takeaway is that once you cut something in half, there is nothing you can do, save eliminating it entirely that will ever again deliver the same raw level of improvement.

In the legal context, for example, we have good reason to accelerate contract review. Start with a standard review that averages 20 minutes and reduce it by 60% through basic interventions (harmonized templates, checklists, playbooks, deviation matrices, etc.). You save 12 minutes per contract. Next, throw on some razzle dazzle AI that reduces average review time by another 60%. You save less than 5 additional minutes. That’s not nothing, especially with large volumes. But it comes at a cost, including the opportunity cost of addressing other chokepoints, constraints, and rate-limiting factors. With that framing, the point seems obvious. Then again, everything is obvious once you know the answer. Diminishing returns are not usually so obvious. What “feels” obvious is: if some is good, more is better. Thus, we regularly encounter organizations doubling down on what already worked and being disappointed when their returns don’t double accordingly.

I love low-hanging fruit. I’m such a fan of incremental improvement we’ve not only segregated LPM team members to specialize in upgrading our delivery infrastructure, we’ve also rolled out a competency framework that formally requires every LPM to measurably contribute to improvement initiatives. Pick the low hanging fruit. But then move on to other low hanging fruit (there’s plenty if you can avoid a fixation on past successes). Ultimately, however, you will need to pursue nonlinear innovation (recall “eliminating it entirely”). There are many small steps on the way to true transformation. But eventually you need to take some big steps, too.

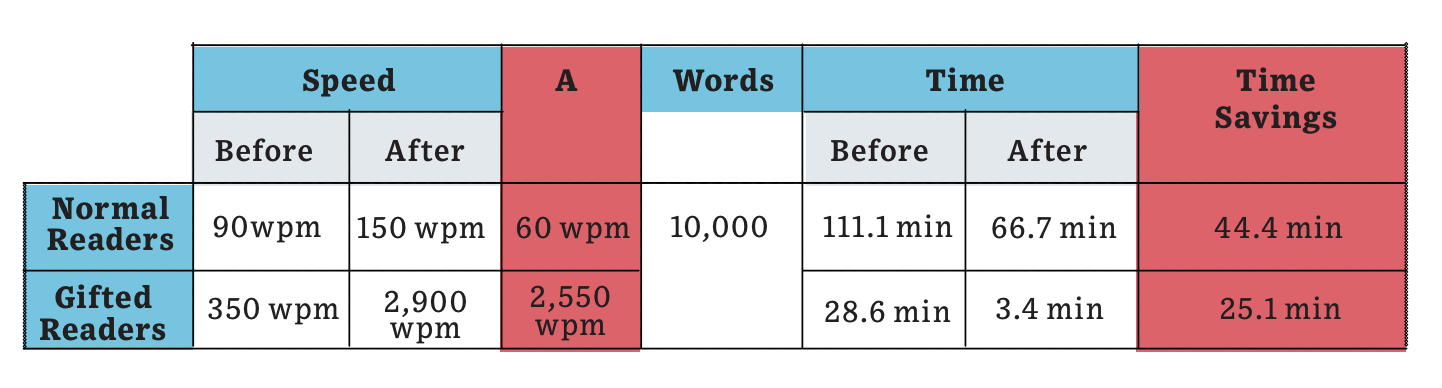

OK, one more silly math problem. I had the good fortune of sitting in on a presentation from Dr. Larry Richards—he of “lawyer brain” fame. If you are unfamiliar with Dr. Richards’ research, I commend it to you. In this presentation, Dr. Richards focused on strength-based teaching. Specifically, he cited a seminal study in which 6,000 Nebraska school children were taught to speed read. Where “normal” students improved their reading speed from 90 to 150 words per minute (+60 wpm, +67%), “gifted” students improved their reading speed from 350 to 2900 words per minute (+2550 wpm, +729%). The moral of the story is leaders should leverage their team’s strengths — i.e., identify and foster the diverse talents of individual contributors. The literature on team performance and work satisfaction supports this conclusion.

But what if we looked at it another way?

What if, instead, the problem we were trying to solve was saving time on a finite task? What if we wanted the school children to get through their prescribed reading so they had time for other activities (music, sports, reading for fun)? Which group is actually saving more time?

Let’s assume they need to read 10,000 words per night (i.e., ~20 pages). The obvious answer is not always the right one, especially when the question changes.

Published April 6, 2020.