Learn about whistleblower programs and how to handle complications with terminated employees.

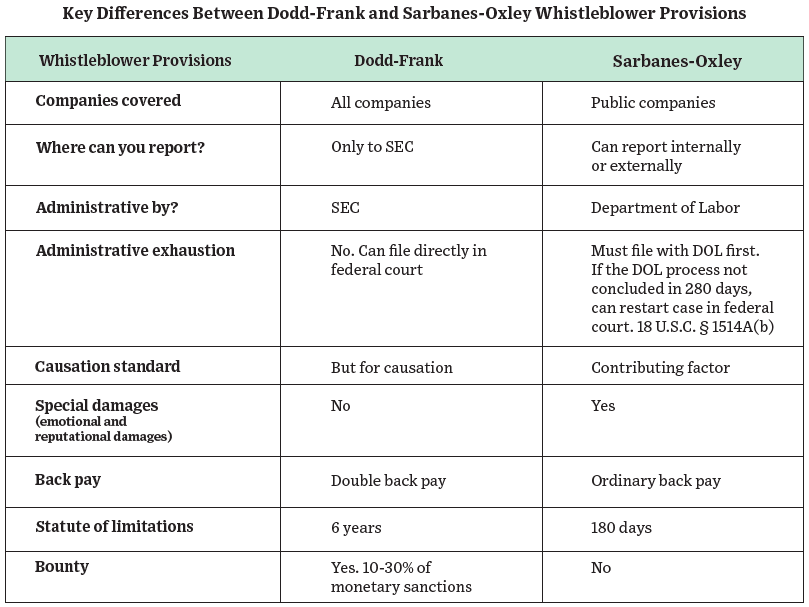

Defending Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank whistleblower claims can be costly and complicated. It can be challenging, for example, for a company to prove that it terminated an employee for performance reasons rather than because the employee reported an issue. This article describes whistleblower programs and recommends actions companies can take to avoid and defend these claims.

Whistleblower Programs

Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) was enacted in the wake of the large accounting scandals in the early 2000s (e.g., Enron, WorldCom) to address corporate fraud and protect investors and capital markets by ensuring corporate responsibility, enhancing public disclosure, and improving the quality and transparency of financial reporting and auditing. The Dodd-Frank Act was enacted in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and included significant financial reform to reduce risk in certain areas of the economy.

To prove a SOX or Dodd-Frank whistleblowing retaliation claim, the complainant must show that (1) he engaged in protected activity; (2) his employer knew of the protected activity; (3) he suffered an unfavorable personnel action; and (4) there is at least an inference that the protected activity was a contributing factor in the unfavorable action. 29 C.F.R. § 1980.104(e)(2)(i)–(iv); Implementation of the Whistleblower Provisions of Section 21F of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Exchange Act Release No. 34-64545 (May 25, 2011), at 18 n. 41.

Protected activity for a SOX whistleblower claim is a lawful act done by an employee to assist in an investigation of conduct that the employee reasonably believes relates to one of six categories of laws

and regulations: four types of fraud (mail, wire, bank or securities); a federal offense relating to fraud against shareholders; or a rule or regulation of the SEC. 18 U.S.C. § 1514A(a). Dodd-Frank protects individuals who provide information about securities law violations to the SEC. 15 U.S.C. § 78u-6(a)(6).

Best Practices to Avoid Complaints

Companies should implement internal reporting practices to help maintain high ethical standards and avoid SOX and Dodd-Frank complaints and other issues.

SOX requires that all publicly traded corporations create independent audit committees. As part of this function, corporations must establish procedures for employees to file internal whistleblower complaints that protect the confidentiality of those who file complaints.

There is good reason for companies to make their internal reporting program robust. Companies should encourage employees to report any issues, and they should respond to employee complaints promptly and conduct thorough investigations. They should report back to the whistleblower as the investigation progresses. Companies should do all they can to keep the reports confidential and protect the anonymity of reporters. Companies should also review proposed actions against the employee to ensure these do not violate whistleblower laws. Finally, when an employee who made a complaint is terminated (or is subject to other adverse action), companies should adequately document the performance or business reason for the action. All of these measures will allow the company to address issues proactively and hopefully avoid whistleblower retaliation complaints.

Defending Filed Complaints

Even companies with high ethical standards and robust internal reporting systems may face SOX or Dodd-Frank complaints. If faced with a complaint, there are a number of defenses a company may raise. Common defenses include: (1) lack of jurisdiction; (2) failure to show the complainant reasonably believed he engaged in protected activity; (3) that the alleged protected activity was not the cause of an adverse personnel action; and (4) for Dodd-Frank claims, that the issue was only reported internally.

1) Jurisdictional Defenses

First, only companies that are securities issuers or affiliates of issuers are subject to SOX. See 18 U.S.C.A. § 1514A (West). Only domestic, publicly traded companies (with more than 500 shareholders and $10 million in assets) or their subsidiaries are subject to Dodd-Frank.

Second, these programs have a limited extraterritorial reach. A company located outside the United States should only be subject to SOX if the misconduct has a significant connection to the United States. Villanueva v. Core Laboratories, ARB No. 09-108, ALJ No. 2009-SOX-006, 2011 WL 7021145, at *10 (ARB Dec. 22, 2011) (refusing to apply SOX extraterritorially in a case involving a foreign citizen who reported allegedly improper transactions between two foreign companies, located in Colombia and the Netherlands Antilles, including perceived under-reporting of income to the Colombian tax authorities.); cf. Blanchard v. Exelis, ARB No. 15-031, ALJ No. 2014-SOX-020, slip op. at *16 (ARB Aug. 29, 2017) (holding that fraud reporting related to a publicly traded, U.S.-based corporation engaged in submitting false claims to the U.S. government in connection with U.S. security and military operations on a U.S. air force base, was “squarely within the type of malfeasance that both SOX and § 806 aimed to deter.”).

Dodd-Frank precedent is less developed, and there is some uncertainty as to its extraterritorial reach. The most recent precedent suggests Dodd-Frank can be applied outside the United States if: (1) conduct within the United States constituted significant steps to further a violation, even if the securities transaction occurs outside the United States and involves only foreign investors; or (2) conduct occurring outside the United States has a foreseeable substantial effect within the United States. See Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 111–203, § 929P(b), 124 Stat. 1376, 1864–65 (2010); Sec. & Exch. Comm'n v. Traffic Monsoon, LLC, 245 F. Supp. 3d 1275, 1294–95 (D. Utah 2017).

2) Reasonable Belief

A company may also raise the defense that the complainant did not reasonably believe (objectively and subjectively) that he engaged in protected conduct. The background and sophistication of the whistleblower should be considered in raising this defense.

To satisfy the objective component of the “reasonable belief” standard, an employee must prove that a reasonable person in the same factual circumstances with the same training and experience would believe that the employer violated securities or fraud laws. E.g. Allen v. Admin. Review Bd., 514 F.3d 468, 479 (5th Cir. 2008) (“Because she is a licensed CPA, the objective reasonableness of [complainant’s] belief must be evaluated from the perspective of an accounting expert.”).

To satisfy the subjective component of the reasonable belief standard, the employee must have “actually believed the conduct complained of constituted a violation of pertinent law.” Day v. Staples, Inc., 555 F.3d 42, 54 n.10 (1st Cir. 2009). As with the objective reasonableness, “the plaintiff’s particular educational background and sophistication [is] relevant.” Id.

Thus, this defense may be particularly effective where there is a sophisticated complainant and the offense complained of is not one covered by SOX or Dodd-Frank.

3) Causation

Under SOX, if a company can prove by clear and convincing evidence that an employee was terminated (or faced other adverse action) for reasons other than protected activity, the complaint will be dismissed. For example, the Seventh Circuit affirmed a Department of Labor ALJ decision where the complainant was terminated six months after she reported fraud, but the ALJ found that the complainant’s poor performance, which began shortly after she began working for her employer and which was never remedied, led to her discharge. Robinson v. U.S. Dep’t of Labor, 406 F. App’x 69, 72–73 (7th Cir. 2010). The ALJ and the Seventh Circuit concluded that because these performance problems preceded her protected activity, the protected activity was not a contributing factor in her discharge. Id.

Under Dodd-Frank, a complainant has a higher burden on causation. He must prove that the adverse action was “causally connected” to the protected activity. Ott v. Fred Alger Mgmt., Inc., No. 11 CIV. 4418 LAP, 2012 WL 4767200, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 27, 2012).

A well-managed employment termination process with supporting documentation is vital to this defense, for both SOX and Dodd-Frank claims.

4) Internal Reporting Not Protected Under Dodd-Frank

On February 21, 2018, the Supreme Court, in Digital Realty Trust, Inc. v. Somers, S. Ct. No. 16-1276, resolved a split in the courts and narrowed the scope of what qualifies as whistleblowing under Dodd-Frank. It held that the definition of “whistleblower” under Dodd-Frank did not include employees who only report internally. Thus, Dodd-Frank only applies to employees who report suspected securities law violations to the SEC.

There can be serious monetary, reputational and employee-morale costs associated with Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank complaints. To help minimize unnecessary costs, it is vitally important for companies to understand the whistleblower provisions of Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank, establish a well-managed internal reporting system and effectively defend these claims.

Published March 8, 2019.